Chiapas in Mexico | Active against the military: "When they're there, my heart calms down"

For many indigenous families in Chiapas, southern Mexico, it's a very funny image burned into their memories: young people from Europe, Latin America, and North America trudging through the mud with their heavy backpacks and getting stuck. They patiently wrestled with the children and playfully taught them to write. Some of them even knew how to cook, but couldn't chop wood. They were and are all part of a special experiment in international solidarity: the Civil Peace Brigades, which have been accompanying autonomous communities in Chiapas since 1995.

For three decades, organized communities in Chiapas have invited international activists to come to their villages as human rights observers for a few weeks. Their simple presence leads to state actors using less violence against the resistant communities and organizations. If that doesn't work, the "brigadistas" document the human rights violations . This allows them to be prosecuted later. The Bricos project (Brigadas Civiles de Observación), organized by the well-known Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas (Frayba) human rights center, celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. But the increasing violence of organized crime in Chiapas is putting the project under pressure.

An uprising in ChiapasThe forgotten and peripheral state of Chiapas suddenly became known worldwide in 1994 when a previously unknown guerrilla group rehearsed an uprising against the Mexican government – and announced this itself on the then-new internet. The EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) demanded the recognition of indigenous rights, autonomy, and an end to the neoliberal policies that increasingly exploited land and resources in Chiapas. To this end, they briefly occupied seven district capitals and, in the long term, thousands of hectares of land. In the early 1990s, not long after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, their way of communicating and naming global problems struck a nerve with a left that was reorienting itself globally. Curious and in solidarity, people from Germany too looked across the Atlantic and listened. Here, in both East and West, several solidarity committees still existed that had supported left-wing movements in Latin American countries from Chile to Guatemala.

As the Zapatistas came under increasing attack from the Mexican state in the months and years following the uprising, it became obvious for many activists to support the sympathetic movement in a practical way. Numerous people traveled to Chiapas in groups or individually, ending up in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, then a small, sleepy town in the highlands.

"That's life in our communities. First, we laugh, then we help."

José Manuél Hernández parishioner from Taniperla

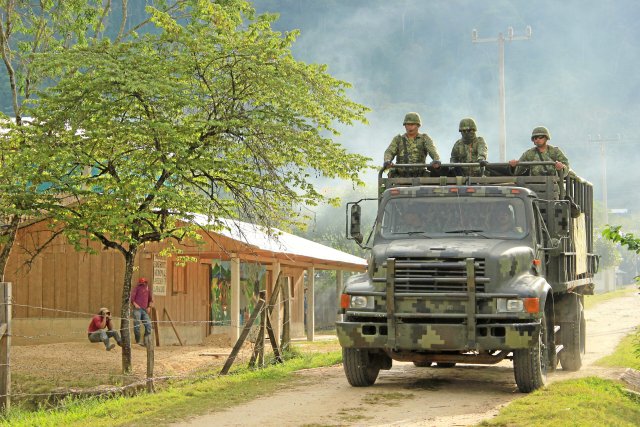

"Suddenly, all hell broke loose here in San Cristóbal," recalls Rosa Rodriguez of the Frayba human rights center. "So much was happening simultaneously." In 1994 and 1995, peace negotiations between the EZLN and the Mexican government took place in Chiapas. It was actually a promising moment, because never before had indigenous voices been so present in the national media. At the same time, there were repeated attacks by the military, and later also paramilitaries, on the Zapatistas and indigenous communities that had not distanced themselves from the EZLN. During these years, the staff of the human rights center and numerous other NGOs hurried daily along dirt roads and tracks through the mountainous state. The road network was unpaved back then, and no one had a cell phone, let alone GPS. They provided humanitarian aid while simultaneously documenting the military's serious crimes: burned houses, disappeared people. In some regions, the Mexican military even dropped bombs.

There was a lot to do. Rosa continues: "And then these people kept coming here from all sorts of countries and even from other parts of Mexico, wanting to support the EZLN, but often not knowing how. One thing led to another."

The first brigadesAmid the violence, various local organizations, including Frayba, established the first Civil Peace Camps in 1995 in Zapatista villages, refugee camps, and other autonomously organized communities. Since the NGOs were at capacity, the activists were supposed to travel to the remote villages, document the situation for a while, and report back to San Cristóbal after a few weeks.

What began as an improvisation became increasingly structured over time. Preparatory groups were formed in numerous countries and actively recruited observers. The volunteers received a further briefing in San Cristóbal and a letter from the bishop in case they were unable to pass the numerous military checkpoints. Then they set off in small groups for 14 days into the "selva," the forests and mountains.

Most of the villages were far from the bumpy roads and could only be reached after hours of walking. José Manuél Hernández from Taniperla laughs when he thinks back to those days. The activists always took twice as long as they did as children. "They came with their rubber boots and got stuck in the mud." Naturally, this caused hearty laughter. "That annoyed some people. But that's life in our communities. First, people laugh because they get help afterward."

The brigadistas usually live in the villages for two weeks, sometimes in a family home, sometimes in their own cottage. These were difficult times; soldiers often entered communities unannounced, searched houses, and stole animals. With the new paramilitary groups, violence increased even further. The Acteal massacre, in which 45 indigenous people were murdered during prayer in a refugee camp run by the pacifist organization Las Abejas in 1997, spread fear throughout Chiapas. "They said they would protect us from the military and something about human rights." José Manuél was eight years old at the time and, as a child, enjoyed playing with the international visitor. "I didn't understand how. But I thought: How good that they would defend us."

Over the years, Frayba has observed that threats and attacks in communities with an observation camp have been less frequent and have decreased. "The Mexican state has an international reputation to lose, so it's a hindrance when soldiers are filmed intimidating or attacking indigenous people," explains Rosa, who played a key role in shaping Frayba's project.

For many communities, however, social aspects also play an important role alongside protection. In Acteal, a "campamento" was set up after the massacre, which still exists today. The organization even built new accommodation for the observers last year. María Vázques Gómez is a survivor of the 1997 massacre and is always happy when the campamentistas come: "I like to eat with them, even if they don't understand me. We don't have any family anymore, and many here are worried about the future. But when they're here, my heart calms down." María understands Spanish well, but speaks the language of the "caxlanes," the "white townspeople," reluctantly. Instead, she speaks with the activists in their own language, Tsostil. Somehow, it usually works out.

Learning processes on all sidesLife in the communities remains a two-way learning process. José Manuél also reported that his life today would not have been the same without the brigadistas. The teachers at his school were violent and impatient. While doing homework with the observers, he realized that learning can also be fun. Years later, he left his village to study.

For volunteers, it is often a formative experience to see how people from indigenous communities defend their autonomy despite the most adverse conditions. Former volunteers report that they themselves learned a great deal through their work – whether through sharing everyday life, working in agriculture, or practicing self-government in Zapatista communities. Many are impressed by the discipline required for long-term resistance and practicing autonomy.

Nevertheless, not everything always went smoothly. Some volunteers found it difficult to adapt to the local circumstances. Gender norms, in particular, are still a regular topic of discussion on both sides. Where there are no showers, people bathe in the river. Bikinis, nudism, or skimpy clothing are anything but common in rural communities, which not only causes surprise or outrage among members of the community being accompanied. In the case of Taniperla and the Zapatista community of La Realidad, hostile neighboring communities used these events to discredit the brigadistas. "In the end, it's machismo," summarizes José Manuél, who himself is strongly critical of the conservative attitudes in his community, but it can also exacerbate conflicts.

To avoid such situations, Frayba developed its own set of rules, which not only provide guidance on appropriate clothing, but also include how to behave during military checkpoints and which tasks fall within the scope of observation and solidarity work, and which do not. The center also created the Frayba Community, a network of currently 30 Mexican and international collectives and organizations that conduct preparatory seminars and information events in their respective countries. On the one hand, participants are aware of what they are getting into, and on the other, this structure also serves as a safety measure in the event of an emergency.

Changing Violence: New ThreatsThe concept of deterrence works up to a certain level of threats and violence. Once this level is exceeded, the presence of observers no longer makes sense, and other measures must be taken. Recognizing this point in a timely manner is crucial for the Human Rights Center.

After a few less turbulent years, violence in Chiapas has steadily increased in recent years. Since 2021, there have been open armed clashes again. This time, the Zapatistas aren't the primary target. Two large drug cartels are primarily competing for control of the territory. At the local level, however, they are colluding with smaller armed organizations, which usually have a regional interest in land. These are often the "heirs of paramilitarism" from the 1990s, as Frayba writes in its latest annual report . This poses a major threat to the autonomously organized communities in Chiapas.

This development is problematic for the human rights monitoring project in several respects. If isolated clashes escalate en route to the monitored communities, the brigades cannot travel to or from the community back to San Cristóbal. A greater problem, however, is that the deterrent effect on actors who are not under state control, such as officials, soldiers, or paramilitaries, is ineffective. Unlike state representatives, the cartels have no reputation to lose. Frayba had to adapt the security measures for the monitors. They continue to document human rights violations, but can no longer be as open as they have been in recent years.

Since taking office, the new governor, Eduardo Ramirez Aguilar , has introduced a new military police force called Pakal in Chiapas, which controls the state with an iron fist. There are currently no more roadside checks by organized crime, and armed clashes have also decreased significantly. However, Frayba's team does not trust the peace. The prisons are extremely overcrowded, and there are increasing signs that the arrests are predominantly of young indigenous men. The human rights center also fears that the recently announced construction of a highway from San Cristóbal to Palenque could trigger a new wave of repression against indigenous environmental activists. The civil organization Modevite, in particular, is already organizing protests, even though construction has already begun.

Currently, around 30 volunteers from Germany alone travel to Chiapas each year. Although there are only two observation camps, overall, too few observers are coming to Chiapas. Current developments, in particular, demonstrate that the brigade concept is by no means a dying breed.

The nd.Genossenschaft belongs to our readers and authors. Through the cooperative, we guarantee the independence of our editorial team and strive to make our texts accessible to everyone—even if they don't have the money to help finance our work.

We don't have a hard paywall on our website out of conviction. However, this also means that we have to repeatedly ask everyone who can contribute to help finance our journalism. This is stressful, not only for our readers, but also for our authors, and sometimes it becomes too much.

Nevertheless: Only together can we defend left-wing positions!

With your support we can continue to:→ Provide independent and critical reporting. → Cover issues overlooked elsewhere. → Create a platform for diverse and marginalized voices. → Speak out against misinformation and hate speech.

→ Accompany and deepen social debates from the left.

Be part of our solidarity funding and support the "nd" with a contribution of your choice. Together we can create a media landscape that is independent, critical, and accessible to everyone.

nd-aktuell